Free Resources Families Are Loving

Books for Every Reader and Interest

Book List

Book List

Book List

Book List

Effective & Fun Learning Resources

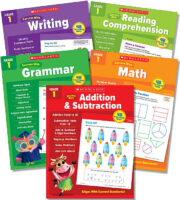

Books | Collections and Libraries | Skills Book Set

Grades

1

$29.7

$34.95

ADD TO CART

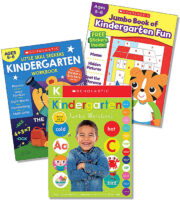

Books | Collections and Libraries | Skills Book Set

Grades

Pre-K - 1

$29.72

$34.97

ADD TO CART

Book List

Books | Collections and Libraries | Skills Book Set

Grades

1

$29.7

$34.95

ADD TO CART

Books | Collections and Libraries | Skills Book Set

Grades

Pre-K - 1

$29.72

$34.97

ADD TO CART

BEST BOOKS & SERIES OF THE YEAR

Book List

Book List

Start With The Best Books By Age

Book List

Book List

Book List

Article

Book List

Article

Book List

Book List

Book List

Article

Book List

Article

Read With Scholastic Book Clubs!

Discover the stories and characters your child will love and earn benefits for their classroom.